Industry Stories

Coronavirus Collides with Automotive Industry

Auto industry leaders just last month feared that COVID-19 would prompt a shortage of vehicles. The large auto parts factories in China’s Hubei province had been shuttered for two months, and more than 80% of the world’s automotive supply chain is connected to China. Additionally, through the beginning of March, there was no indication of lower demand.

Six weeks later, automakers are still fearful but their worries have flipped. It is clear now that their problem is oversupply.

This matters because auto manufacturing is commonly used as a measure for the economy’s health, given how many industries feed into it and its large number of workers. Analysts estimate more than 8 million people are employed manufacturing automobiles and that each of those jobs supports about five jobs in other industries. The output of the automotive industry would have a GDP of near $3 trillion if it were its own country. But that number is now shrinking.

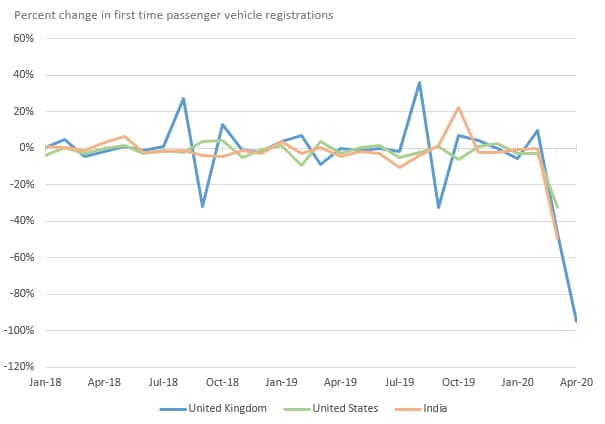

European new car sales slid 52% for the month of March and vehicle registrations were down 56%. Registrations are also lower in the United States and India (Figure 1). Italy’s sales in April have declined 98%. In India, March motor vehicle sales recorded their biggest year-over-year drop with a 58% decrease. That is particularly difficult for an industry where car sales have been declining year-over-year since November 2018. Compounding these issues, 26 U.S. states (comprising 56% of the country’s retail sales) are allowing only remote or online sales. New car sales in the U.S. for the month of April are expected to be down about 50% compared to 2019.

Figure 1. First time vehicle registrations are down dramatically.

Source: OECD (2020), Passenger car registrations (indicator).

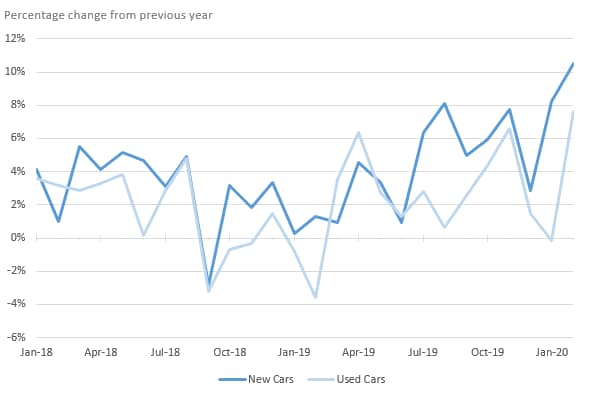

In a typical recession, used car sales see a year-over-year sales increase suggesting a substitution effect. During the Great Recession, dealer year-over-year revenues for used cars in the U.S. increased for the first four months. The economic impacts of the coronavirus are different.

In the U.S., used car sales typically peak in March. These used cars sales were flat in January and up 7% in February (Figure 2). Year-over-year sales of used cars have been increasing since March 2019. March 2020 U.S. sales figures will not be out until later in May. However, used car sales in Europe mirrored the drop in new car sales for March in the five largest European markets. This indicates that the pandemic is driving down overall demand for vehicles. Because of the COVID-19 lockdowns, people are driving less and making less use of the cars they have. Aside from the current crisis, a contributing factor to this lower demand is that people are keeping their cars longer. From 2009 to 2017, the average age of a light-duty vehicle in the U.S. increased by 13% to 10½ years.

Figure 2. New and used car sales in the U.S. were poised for growth in early 2020.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau via Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

While we have evidence that demand for motor vehicles in Europe is down, the U.S. data is not yet conclusive. Overall, data suggests that prices in most markets for new vehicles are too high. Low financing rates and low gasoline prices are encouraging some new car sales in the U.S. However, the force exerted on demand by the coronavirus lockdowns is much larger.

There does not seem to be a good solution to this problem. It is easy to suggest that manufacturers reduce production in the face of lower demand. However, that lower production will invariably lead to a shrinking of the economy due to its large workforce. With lower incomes or lost jobs, those in the automotive industry will spend less, which reduces the income of others in the economy and creates a vicious cycle. Someone, somewhere is going to have to take a loss.

This creates a dilemma. If political and business leaders take no action, each group loses less separately, but the economy loses more in total. If leaders put the burden on one group of stakeholders, that group takes a catastrophic loss, but the whole economy loses less. Of the stakeholders — which include governments, automotive manufacturers, dealers, and automotive workers — the best positioned to absorb these losses are governments, as was done in the Great Recession. They can defer and spread out losses, which can be recovered by future taxes, in a way that is the least bad for the economy. This action makes sense for governments including Germany, Japan, and the United States, whose automotive industries make up as significant portion of their manufacturing sectors. In Bangladesh, leaders should consider similar actions with the textile industry. In this way, we can flatten the curve on losses to lessen the severity of the recession.